- Home

- Carl Deuker

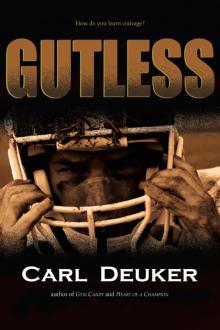

Gutless

Gutless Read online

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part Two

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Part Three

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Part Four

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Part Five

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Sample Chapters from SWAGGER

Buy the Book

Singular Reads

About the Author

Copyright © 2016 by Carl Deuker

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Cover photograph © 2016 Getty Images

Cover design by Jim Secula

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Names: Deuker, Carl, author.

Title: Gutless / Carl Deuker.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016. | Summary: “With both good speed and good hands, wide receiver Brock Ripley should be a natural for the varsity team, but he shies from physical contact. When his issues get him cut from varsity, he also loses his friendship with star quarterback Hunter Gates. Now a target for bullying, Brock struggles to overcome his fears and discover that, in his own way, he is brave enough.” —Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015031264 | ISBN 9780544649613 (hardback)

Subjects: | CYAC: Fear—Ficition. | Bullying—Fiction. | Football—Fiction. | Friendship—Fiction. | High schools--Fiction. | Schools—Fiction. | BISAC: JUVENILE FICTION/ Sports & Recreation / Football. | JUVENILE FICTION / Social Issues / Bullying. | JUVENILE FICTION / Boys & Men. | JUVENILE FICTION / Social Issues / Friendship.

Classification: LCC PZ7.D493 Gu 2016 | DDC [Fic]—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015031264

eISBN 978-0-544-86982-0

v1.0816

For Beth, Noah, and Leila

The author wishes to thank Ann Rider, the editor of this book, for her help.

I don’t know what it is, but I do know that Hunter Gates had it. Not just because he was bigger and stronger than everybody else. He had it in the way he cocked his head, the way he looked at you, the way he didn’t look at you. He let you know that he came first and everyone else followed and that was how it was meant to be. It’s why I never liked him, not in middle school, not in high school. And it’s also why—until he went full throttle after Richie Fang—I wanted to be his friend.

It was a hot June day when Hunter Gates showed up. I was hanging out with Trevor Marino, Austin Pauley, and the McDermott twins—Rory and Tim. Eighth grade was over; Whitman Middle School was over. You’re in between things when you’re that age: you can’t wait to grow up, but you’re scared of it too.

We’d met at the skateboard park by the library at noon and then drifted down to Gilman Park. We had no plans, so we killed time in the shady area between the wading pool and the basketball court, where a half-dozen shirtless high school guys were playing a full-court game.

Every once in a while, one of us would disrespect another guy—say something about his sister’s body or his own zits. It was a joke, but there was always the taste of truth to it, so whoever got dissed would chase his tormentor around, pretending to be mad enough to fight. Sometimes the chase would go through the wading pool, which ticked off the mothers hovering over their toddlers. They glared at us, and finally Mrs. Rojas—the woman who’d supervised the wading pool for a million years—told us to leave.

We argued that we hadn’t done anything wrong and that America was a free country, but she threw up her thumb like an umpire making a call at home plate. “Out of here. You’re too old to be hanging around a wading pool.”

Rory McDermott had brought along his soccer ball—we’d all played on the Whitman Wildcats, our middle school’s soccer team—so we wandered over to the soccer field and started kicking it back and forth.

Hunter Gates was two years older than us, so he was heading into his junior year. He was bigger, stronger, tougher, and meaner than anybody else.

Every time I saw Hunter, I remembered Jerry Jerzek. There was nothing special about Jerry. He wasn’t smart or funny or athletic. He was just a good guy.

I don’t know what Jerry did to Hunter—or if he even did anything. But in seventh grade, right after Halloween, Hunter got on him, and that meant that Hunter’s friends got on him too. They said that his ears were too big, that he crapped logs that clogged the school toilets, that his mother’d had sex with an iguana. And then they started calling him Jerry Jumper.

Nobody knew what the joke was. But every time Hunter or one of his buddies—and he had about a dozen in his posse—spotted Jerry, they’d scream, “Jump, Jerry, jump!”

Jerry tried to ignore them, but then they’d come at him and play-slap him on the side of his face until he finally jumped as if he were on an invisible pogo stick. Once Jerry was red in the face and sweating, Hunter would tell him he could stop. “We’re just kidding you, Jerry. No hard feelings.”

After Hunter and those guys got on him, nobody wanted to be seen with Jerry. It was as if he had diarrhea or something worse. I once saw him throwing up in the bushes before school. Not long after that, he started skipping school, and in February he transferred to McClure on Queen Anne Hill.

In my fourth grade science class, my teacher once emptied a bottle of iron filings onto a piece of paper and drew a magnet back and forth above them. The filings danced around the paper, drawn to that magnet wherever it went. That’s how it was with Hunter Gates. He drew people to him, even if what he was doing made your insides churn.

The reason was simple. Name a sport where a ball bounced, and Hunter wa

s great at it. Not good—great. Football was his best sport. His father started grooming him to be an NFL quarterback from the day he was born. Hunter’s Crown Hill junior football team won the league title every year, and then he was great again in middle school. As a high school freshman, he took Crown Hill High from city laughingstock to the brink of the playoffs. Everybody figured he’d just go on being great, but his sophomore year was mediocre. Not bad, but not good—he was just another quarterback. It was the first time he’d been ordinary.

That June day, while I kicked the ball around with the McDermott twins and the other guys, Hunter and his father unpacked their gear and started throwing a football back and forth. His father was a big-shot attorney for an oil company that did fracking in North Dakota, but he didn’t ignore Hunter. At every game and most practices, he was on the sidelines—one of those parent volunteers who do nothing but work with their own son.

Whenever I’d seen Hunter’s father at a game or practice, he had his arms crossed in front of his chest, a baseball cap pulled down over his eyes, and a grim look on his face. He didn’t scream, but he never smiled, either. Tough love is what my dad called it. “His kid has a ton of talent, so he doesn’t want him to waste it. Hard to blame him for that.”

All of Hunter’s passes that late June day were bullets, straight as a string. But no matter how well he threw, his father saw something wrong. His arm wasn’t high enough; he was stepping too far forward; his footwork was slow.

I didn’t want a father like that, but I did wish my father could go to the park with me, kick a soccer ball around, and just be a dad.

I used to do everything with my dad—basketball, baseball, soccer, hiking, bike riding. He’d been a soccer player at Eastern Washington—sweeper—but he played any sport I wanted to play, except football. My mom made football off-limits because of all the news about concussions. It was no big deal, because in those days I didn’t like the game much, especially the tackling part. My dad was good with his hands too, so on rainy days we built bookcases and made wood toys in the basement.

We don’t do any of those things anymore.

Now he needs leg braces to help him stand and arm braces to help him keep his balance. It takes two minutes for him to get out of his chair in the living room and walk to the kitchen. He still has his job at the bank, but for a while they were trying to get rid of him. Unless a cure is found, he’ll get worse and worse, until one day he won’t be able to walk at all. That day might be twenty years away, and it might be five years, but it’s coming.

In a way he got sick all at once, but in a way he didn’t. I’d suspected for a long time that something was wrong, and so had my mom. We’d all pretended nothing was happening, until the day came when we couldn’t pretend.

In sixth grade, Mr. Dong was my science teacher. At first, I didn’t do much more than laugh at his name. But in October, I started listening to him, and he got me interested in science. I joined his science club, and my dad and I built wooden mazes for the classroom rats. Once the mazes were built, I came up with a series of experiments to figure out how quickly rats learn. I put different food rewards at the end of the runs, and I changed the difficulty level of the mazes. I timed the rats and made graphs in Excel. Other teachers came and judged the projects, and I took first place, beating out Anya Lin, who usually won everything.

When my parents found out I’d get a medal at an evening assembly, they insisted that we go. The chess club, the math club, the band, and the orchestra also gave out awards that night. Science club was last. After what seemed like forever, Mr. Dong took the podium. Before handing out awards, he talked about the great future that awaited all of us. My medal looked like one of those chocolate coins wrapped in gold paper you can get at Trader Joe’s, but it felt good to hear Mr. Dong say “Brock Ripley” and to look out and see a roomful of people clapping for me.

After the awards ceremony, we walked back to the Honda. My mom was telling me how proud she was, but my dad stayed quiet. I didn’t think much of his silence; over the past months, he’d become quieter and quieter.

When we reached the car, I climbed into the back seat, while Mom slipped into the front passenger seat. We sat as my dad stood outside, his hand on the car door. We waited for about a minute, wondering why he didn’t just open the door and climb in. Finally, my mom reached over and pressed the button that lowered the window. “Is something wrong?”

My dad’s voice was shaky. “My hand—it’s sort of locked.”

My mom got out, moved around to the driver’s side, and helped him open his hand up. As she did, I heard him whisper, “What’s happening to me?”

After that, things changed rapidly. Besides being a soccer player, my dad had been a middle distance runner at Eastern Washington—the two mile was his race. For as long as I could remember, he’d run thirty minutes every morning, and when he neared our house he would sprint the final one hundred yards, his legs firing like pistons. I was always the fastest kid in my class for fifty yards, but after that I grabbed my side and was done. He was powerful in a way I hoped someday to be.

In the weeks following the awards ceremony, he’d go out to run only to come back after a few minutes. He’d sit on the sofa and rub his legs. When I asked him what was wrong, he’d say he was fine, but by the middle of summer he’d stopped running entirely.

In the summer, it stays light in Seattle until almost ten at night. Most evenings, I hung out with my friends, but if nothing was doing with them, my dad had always been willing to go to the park after dinner and kick around a soccer ball.

But that summer, he changed. His back was stiff . . . his leg hurt . . . he had work to do for the bank. After he’d turned me down a half-dozen times, I stopped asking. Soon, he wasn’t able to prune the hedges in the backyard, mow the lawn, or lift heavy packages.

My dad and I both have dark hair and eyes. In the summer, both of us get deep tans. He stayed pale that year, and his eyes lost color, changing from dark brown to gray. He drove differently, too. He’d always been a fast driver, looking to beat the light by cutting in front of drivers who were going too slowly for him. Now he poked along in the far right lane, his foot resting on the brake.

He hardly ate, and he went from looking strong to looking skinny. Mom wanted him to go to the doctor; I heard them arguing when I was upstairs in my room and they were down in the kitchen.

Right before school started again, my mom gave me the news. “Your father is going to spend a couple of days in the hospital. They’re going to run tests to find out why he isn’t feeling well. Don’t worry, though. They’ll get him the right medicine and everything will be fine.”

I believed her. I was certain the doctors would figure out what was wrong and make him right. But when my dad came home two days later, he called me into the kitchen, had me sit down in a chair across from him, and told me he had something called Steinert’s disease. “My muscles stiffen up quickly, and they twitch when they shouldn’t. I’m losing strength.”

“But medicine can make you better, right?”

He frowned. “Maybe someday, but not today.” He forced himself to smile. “That’s the bad news. But there’s good news too. This disease progresses slowly. I’m going to live for a long, long time. So for someone who is really unlucky, I’m actually very lucky. There are people who have it a lot worse, so I’m not going to feel sorry for myself. And I don’t want you to feel sorry for me either. Okay?”

There were five of us at Gilman Park on the day that Hunter Gates appeared. Five guys aren’t enough for a real soccer game, so we did what we always did when we were short-handed—I stood in goal, and the other guys took turns firing shots at me from about twenty yards out. I’d been the goalkeeper for the Whitman Middle School team, so I was in goal at Gilman.

When I’d first played for Whitman, I was a right forward. My speed made me a threat. When one of our fullbacks booted the ball downfield, my job was to outrun everybody to the ball. As long as I avoided being of

fside, I’d be able to score goals on a regular basis.

That was Coach Nelson’s strategy, but it never panned out. I don’t know why, but I can’t settle a ball without coming to a complete stop, or close to it. That gave defenders time to catch up, and once it became a battle for the ball, I lost. I was never good at the elbowing and pushing part of soccer. Same thing with wrestling or fighting for rebounds in basketball. I wanted to be a guy who left some skin in the game, but when it came to it, I always pulled back. “Toughen up, Brock!” Coach Nelson would holler. But time after time, I’d have the ball taken away. Coach Nelson would throw his head back in agony; the parents of the other kids would groan; my teammates would glare.

In seventh grade, Coach Nelson put Alan Page out on the wing and stuck me on the bench. Alan isn’t nearly as fast as I am, so he didn’t break free often. But when he got the ball, he fought off defenders, and his shots sometimes found the back of the net. Once he took my spot, I wandered the sidelines, one of the useless guys.

Then I caught a break. Early in the eighth grade season, Trevin Winehart, our goalie, didn’t show up for a game. Coach Nelson looked long and hard over his bench players before pointing at me. “Brock, get in the goal.” That game, I stopped every shot—okay, none of them were too hard—and we won 2–0. Winehart came back, but I’d become the Whitman goalkeeper.

With me as keeper, our team clicked. On offense, somebody would sneak a goal or two across, and on defense I’d stop whatever shots came my way.

For the first weeks of our winning streak, I thought I was a natural goalkeeper. Good hands, quick reactions, foot speed—I had it all. Then came the game against Jane Addams Middle School.

Those guys were rough right from the start. One of their forwards, a stocky guy with blond hair, always looked for a chance to give me a little shot with his forearm when the ref wasn’t looking. Coach Nelson had warned us about them beforehand. “Don’t let these guys intimidate you. They hit you, you hit them back harder.”

The McDermotts and those guys dished out as much as they took. I wanted to be tough like the McDermotts, tough like everybody else. But the blond guy kept hitting me every chance he got, and I never made him pay. Next time, I’ll show him. That’s what I told myself, but the next time was just like every other time.

Golden Arm

Golden Arm Swagger

Swagger Gym Candy

Gym Candy Night Hoops

Night Hoops Payback Time

Payback Time Gutless

Gutless Runner

Runner High Heat

High Heat Painting the Black

Painting the Black