- Home

- Carl Deuker

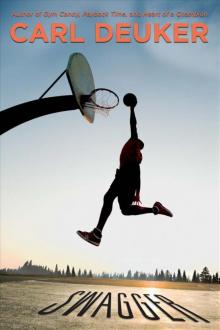

Swagger

Swagger Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

PART ONE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

PART TWO

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

PART THREE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

PART FOUR

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

PART FIVE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Do You Need Help?

Read More from Carl Deuker

About the Author

Copyright © 2013 by Carl Deuker

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Deuker, Carl.

Swagger / Carl Deuker.

p. cm.

Summary: High school senior point guard Jonas Dolan is on the fast track to a basketball career until an unthinkable choice puts his future on the line.

ISBN 978-0-547-97459-0

[1. Basketball—Fiction. 2. Sexual abuse—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.D493Sw 2013

[Fic]—dc23

2012045062

eISBN 978-0-544-15154-3

v1.1113

For my mother,

Marie Milligan Deuker,

1923–2007

I would like to thank Ann Rider, the editor of this book, for her advice and encouragement.

PART ONE

1

ALL THIS STARTED ABOUT A year and a half ago. Back then I was a junior at Redwood High in Redwood City, a suburb twenty-five miles south of San Francisco. In those days, before Hartwell, before Levi, I took things as they came, without thinking a whole lot about them. Maybe that’s because most of the things that came my way were good.

Take school. I didn’t much like my classes at Redwood High, but I did like being the starting point guard on the varsity basketball team. And I loved seeing my name, Jonas Dolan, in print in the sports section of the Redwood City Tribune.

The main reason school never seemed to matter too much had to do with my father’s job. He made good money working for a sand and gravel company down at the Redwood City harbor. I liked visiting him at work—liked the noise of the cement mixers, the shouts of the men, the nonstop activity of the plant. I figured that once I graduated from high school, my dad would get me a job there. He thought so too; lots of times we talked about working together.

Not that I was a total slacker in the classroom. You can’t play if you don’t earn your credits, so I studied enough to stay eligible. Halfway into my sophomore season, I’d cracked the starting lineup on the varsity basketball team. For the rest of that season, I averaged eight points and three assists per game. During the first half of my junior year, I’d pushed those numbers up to eleven and six, making me one of the top four point guards in a decent league.

Then I had my breakout game.

It came in mid-January against Carlmont, a middle-of-the-pack team like us. Everyone expected the game to be a nail-biter, with one team winning by a few points. Instead, we trounced them. I scored fourteen points, pulled down five rebounds, and had nine assists, while turning the ball over only once. It was the best game of my life, but I didn’t feel as if I was playing out of my mind. Instead, it was like everybody else on the court was wearing lead shoes, while I was lighter than air.

2

THAT CARLMONT GAME HAD BEEN on a Wednesday night. I floated through school the next day and through practice after school. As I was leaving the gym, I heard Coach Russell’s voice. “Jonas Dolan, come to my office.”

He sat me down across from him, pulled on his big ears a couple of times, scratched his gray hair, and finally asked me what I planned to do when I finished high school.

“My dad works at the sand and gravel. He can get me a job there.”

“No plans for college?”

I didn’t like the way Coach Russell said that, as if there was something wrong with people who didn’t go to college. “Neither of my parents went to college, and they’ve done okay.”

Coach Russell started waving his hands around, his face reddening. “Completely true, Jonas. I know your dad; I know Robert. He’s a hard-working man. And I’ve met your mom, though I can’t say I know her. There’s nothing wrong with working with your hands. But you’ve got your whole life to work. If you go to college, you can be a kid for a while longer. That sand and gravel plant isn’t going anywhere.”

As he spoke, I thought about what it would be like to work eight hours every single day. Was I ready to do that? Still, I shook my head when he finished. “I’m lucky to get Cs, Coach. I’m no student.”

“But you could be a good student, Jonas. I talked to your teachers; they all say that.”

After he said this we both sat, the seconds ticking away. Then he leaned forward, a glint in his eyes. “If you could play basketball in college, would that make a difference?”

I was so startled by the thought that I laughed. “Sure it would, but there’s no college that wants a six-foot white guy who can’t dunk. The worst player on a crappy team like Oregon State is way better than I am.”

Coach Russell put his big hands flat on his desk and leaned back. “Jonas, Oregon State is a Division One school. I’m not saying you’re D-One material. However, there are three hundred Division Two schools that have basketball teams. Many are top-notch private colleges—great places to get an education. You’re a hard-nosed ballplayer; you’re the most coachable kid I’ve had in years; your game is coming on like gangbusters. Those are all qualities that D-Two coaches look for.”

As he spoke, a strange thrill raced through me. I was a step slower than the black guys from Oakland and San Francisco I’d played against, but Coach Russell was right—those guys were headed to major colleges. Some of them might even end up in the NBA. They wouldn’t even consider Division II ball.

Then reality hit: college costs big bucks.

“Coach, my parents don’t have money for something like that.”

He smiled. “Ever heard of a scholarship, J

onas? And I mean a full ride—room and board. If you’re not interested, then that’s that. But if you are, I’ll help. Division Two coaches don’t come looking for players. I’ll need to get some game film of you and write you a letter of recommendation. You’ll need to request a copy of your official transcript. If we send all that out to fifty schools, you might get a call or two.” He looked at me from under his bushy eyebrows. “You’ll never know unless you try.”

3

I KNEW MY MOM WOULD BE crazy happy when she heard what Coach Russell had said about the possibility of college, but with my father things were more complicated.

In September, just as school was starting, the chute on my dad’s cement mixer had swung free and smacked into his leg. The impact fractured his kneecap and caused internal bleeding in his leg. My dad needed two operations, and afterward his leg had become so infected that the doctors nearly had to amputate. He didn’t lose the leg, but when he came out of the hospital, he walked with a limp.

My dad didn’t go back to work until November. For a week, he tried to drive a mixer, but he couldn’t do it, so his boss gave him an office job as a dispatcher.

I figured everything was okay, but right after the New Year, he started coming home after my mom and I had already eaten, looking both tired and worried. He smiled when he saw me, but it was a forced smile. As soon as I went into the den to watch television, he and my mom would whisper together in the living room, their voices low.

I tried to tune them out, but I couldn’t. Was he sick? Not just injured, but really sick? Or was it something else? I’d had friends on the basketball team—Mark Westwood was one of them—whose parents had gotten divorced, and their kids had had no clue it was coming. Was that it?

One night I was watching the Warriors play the Thunder when the front door opened. My dad said hello like he usually did; then he went into the living room, and there was whispering between Mom and him. I tried to concentrate on the game, but my stomach churned with worry. I was about to head to my room to get away when his voice called out. “Come out here, Jonas. You need to know this.”

I sat in the big chair across from him; my mom sat next to him on the sofa, her hand in his. He looked at her and then turned to me. “Jonas, two men from the national headquarters of the sand and gravel have been around the past few months. They’re both college guys, brainy types whose job is to figure out how to make more money for the company. One idea they’re kicking around is to computerize the dispatch part of the business. If they go that route, I could be out of a job.”

I looked at him in disbelief. “That’s crazy. You’ve been there twenty-five years. You know more about that place than—”

He raised his hand, signaling me to stop. “Jonas, I’m telling you this because you’re not a kid anymore, and you need to know the truth. It’s about money, nothing else. But whatever happens, we’re going to be fine.” He looked at my mom. “We’re going to be just fine.”

4

THAT CONVERSATION HAD TAKEN PLACE two weeks before the Carlmont game. Ever since then, I’d heard my dad complain to my mom about some change the college guys were proposing. I could hear bitterness in his voice. Now I had to suck up the courage to tell him that I wanted to be a college guy.

I would have done it, too. But as I stepped inside the front door that night, my dad was slumped on the sofa, his face looking more lined than ever. My mom sat in the chair across from him. Her mouth was turned down and her short blond hair was mussed—she works as a hairdresser, so it’s never that way. They’d been talking in low voices when I opened the door, but the room fell silent once they saw me.

I said hello, pretending not to have noticed anything, and then headed into the kitchen. My mom followed me, asking me what I wanted to eat. After she’d stuck an enchilada dinner into the microwave, she put silverware on the table in front of me. As she moved around the kitchen, her eyes were watery, as if she was on the verge of tears. That wasn’t like her, either. In my whole life, I’d seen her cry only a couple of times.

For the five minutes the frozen dinner spun around on a glass plate, she asked the usual questions about my day. As we talked, I heard my dad in the front room rustling the pages of the newspaper.

When my dinner was ready, my mom sat down across from me. I took a couple of bites before putting down my fork. “Did they fire him?”

She shook her head. “No, they didn’t.”

“So what’s wrong?”

She spoke in a low voice. “They hired a whiz kid from Cal Berkeley. He’s going to try to merge customer information and area maps and cement-mixer capacities and traffic flow and who knows what else into some computer software program that would make everything more efficient. If he succeeds, they won’t need your dad to figure out the timing or the routes or—” She stopped and shook her head.

5

MY NEXT GAME WAS FRIDAY night against Sequoia High, our cross-town rival. As we came out of the locker room to loosen up, Coach Russell pointed to the top row of the stands. I followed his finger and spotted a stocky man with a movie camera mounted on a tripod. “That’s my brother Jim. He’ll be filming you.”

The place was rocking, lights and sounds filling every inch of the gym, but as I moved through our pregame drills, all I felt was the camera trained on me like a rifle. I looked down at my hands just before tip-off, and they were shaking.

The jitters stayed with me through the opening minutes of the game. On an early fast break, I dribbled the ball off my foot and out-of-bounds. The next possession, I hoisted up an air ball from about twenty-eight feet. “Settle down, Dolan,” Coach Russell hollered, palms facing down.

Sequoia’s guard, Alex Fuentes, brought the ball up. Just as I went for a steal, Fuentes crossed over on me and drove to the hoop for a lay-up. As he ran back to play defense, Fuentes smirked at me, as if I were nothing.

That smirk snapped me out of my funk. For the rest of the half, I was in his face on defense and eating him alive on offense. I hit a step-back jumper at the three-minute mark, and then faked the same shot only to blow by him for a lay-up the next time down. We were trailing by seven when Fuentes gave me his little grin again; at halftime we were up by four points. During that stretch, I totally forgot the camera.

And I didn’t think about it during the second half, either. A point guard isn’t a scorer; my main responsibility was to get the other guys going, particularly Mark Westwood, our center. Early in the third quarter, I gave a couple of nice lobs over the top that resulted in easy dunks. After that, I spread the ball around, getting different guys on the team touches. Everything clicked, and we ended up winning, 58–39. My line: thirteen points, nine assists, and three rebounds.

Afterward Coach Russell high-fived us all. “Great game! Great game!” As the locker room emptied, he motioned for me to stay behind. Once we were alone, he told me he was going to make DVD copies of the video his brother had shot and get them in the mail. “Shouldn’t someone edit it first?” I asked. “I screwed up royally in the first quarter.”

Coach Russell shook his head. “Trust me, Jonas. Sending a complete game is the way to go. Coaches will know we’re not hiding anything. Honesty matters.”

That was like Coach Russell, always completely straightforward. I didn’t think much of it in those days. I thought all adults were that way. I didn’t know then what I know now.

In the locker room, I changed into street clothes and then went to an arcade with Mark where we played video games and talked hoops. “You might make all-league next year,” Mark said. “You’re playing lights out.”

When I returned home later that night, the house was dead quiet. I assumed my parents were asleep, but when I turned on the light, I saw my dad sitting on the sofa with his leg up on an ottoman, a heating pad wrapped around it. The instant the light went on, he took his leg down and unwrapped it.

“You okay?” I said.

“I’ve been better,” he answered. Then he smiled. “I was at your game

tonight.”

“You were? I didn’t see you.”

“I had to leave at the end of the third quarter. Damn leg. You stunk it up early, but you sure came on. Did you finish strong?”

“We killed them.”

“I figured as much.”

In the dark room, in the quiet, I almost told him about the video and the letter to the colleges. But before I could find the words to start, my dad stood. “Well, I’m off to bed. You made your old man proud today, Jonas.”

6

I SPENT SATURDAY AT THE YMCA on Hudson Avenue playing pickup games. One odd thing happened: Alex Fuentes, the guard for Sequoia High, came in after I’d been there for half an hour. It was tense between us for a few minutes, but then we both relaxed, and he turned out to be a good guy. “You thought I was dissing you?” he said at the water fountain between games. “I’d never do anything to get anybody ticked off, especially not you. You’re the toughest matchup I’ve had all year.”

Monday morning, right before lunch, I got a note calling me to the coaches’ office. When I stepped inside, Coach Russell held up a couple of pages of paper and waved them around. “I printed a list of Division Two colleges that give scholarships. There are some in every part of the country. You have any preference as to where you want to go?”

“Wherever you say, Coach.”

He shook his head. “No, Jonas, not wherever I say. You’re the one who’s going to live there.”

In fifth grade, I’d done my state report on Vermont, filling twenty pages with pictures of rolling mountains that seemed to be on fire because of the autumn colors of the trees. “Are any in Vermont?” I asked.

“There are a couple in Vermont, and even more in Massachusetts and New Hampshire and Connecticut. But are you sure you want to live in New England? It gets cold there.”

I’d never once thought of living in New England, but as soon as he said the words, I somehow knew that New England was the place for me.

“New England,” I said.

Golden Arm

Golden Arm Swagger

Swagger Gym Candy

Gym Candy Night Hoops

Night Hoops Payback Time

Payback Time Gutless

Gutless Runner

Runner High Heat

High Heat Painting the Black

Painting the Black